Through this workshop participants will learn how to manage their personal data online. What is the most important thing to do regarding their own data ? And what is less dangerous, less important for instance.

General Objective

Preparation time for facilitator

Competence area

Time needed to complete activity (for learner)

Name of author

Support material needed for training

Resource originally created in

Introduction

This workshop will be divided into two activities

- An exploration of participants’ Google and Facebook accounts to showcase the amounts of data taken by collected two companies

- A walking debate, to get a sense of participants’ opinions

Facilitation tips: Concerning the first activity, we recommend you guide participants (for those who want it) the change their account settings in order to limit the amount of data that can be collected. Going further, you can also explain how to choose a more ‘ethical’ browser and a search engine and how to configure them.

Context

Who said the following:

We know where you are. We know where you’ve been. We can more or less know what you’re thinking about.

Answer: Eric Schmidt, president of Alphabet (parent company of Google) in 2010. Google wishes to give you a personalised experience and to this, the company amasses as much data as possible on its users as they use its free services. Facebook practices the same kind of relationships with you. Indeed, according to a study by PNAS, with 10 likes worth of digital footprint, an algorithm proved itself to be better at determining a user’s personality than a work colleague.

With 100 likes, the algorithm is more effective than a family member and with 230 likes, Facebook ‘knows’ a user better than their spouse. But what do Facebook or Google do with all this information? It’s quite straightforward: they sell it to data brokers which cross-reference it with other sources and sell it to advertisers who will then create targeted advertising (see the workshop plan ‘Targeted and Mass Advertising‘). Now, let’s see what information Facebook and Google actually have on us.

What do Google and Facebook know about us?

Let’s start with Google. Maybe participants will know already that Google Maps tracks our movements by default. Start by showing this image:

This is the kind of information we can find by going to our Google account and checking our map timeline. Ask your group to check the link by logging in to their Google account. They’ll be surprised! Google knows a lot more about you than your simple Maps history – not just where you’ve been. Let’s look a little closer. Have participants go to Google Activity. Once again, in order to ‘make services more useful for you’, Google saves constantly and by default:

- Web & App Activity: meaning your Google searches, as well as Chrome history if you use it.

- Location History: Slightly different from the map timeline linked above, since we here learn that Google ‘saves where you go with your devices, even when you aren’t using a specific Google service, to give you personalized maps, recommendations based on places you’ve visited, and more.’

- Managing contact info from your devices: Google saves a copy of your contacts, of your agendas, a list of apps installed on your phone, your music as well as various other miscellaneous information concerning your device such as how much your battery is charged. The company claims to collect of this information in order to better personalise users’ search results and suggestions. We might wonder how knowing how much a battery is charged helps with search results.

- YouTube History: Google ‘saves the YouTube videos you watch and the things you search for on YouTube to give you better recommendations, remember where you left off, and more.’

Check these links with the group and ask them verify together the data Google has on them. According to the users and how much they use the various services, they will find different amounts of information. Ask them if they realised how much information Google had about them.

You could demonstrate on a large screen with your own account, but be careful before doing this, as the group will be able to see all your information! A smart way around this would be to create a new account in advance to demonstrate. Allow participants to navigate and realise all the information that has been collected on them. You could also help them to configure their account to limit what Google collects.

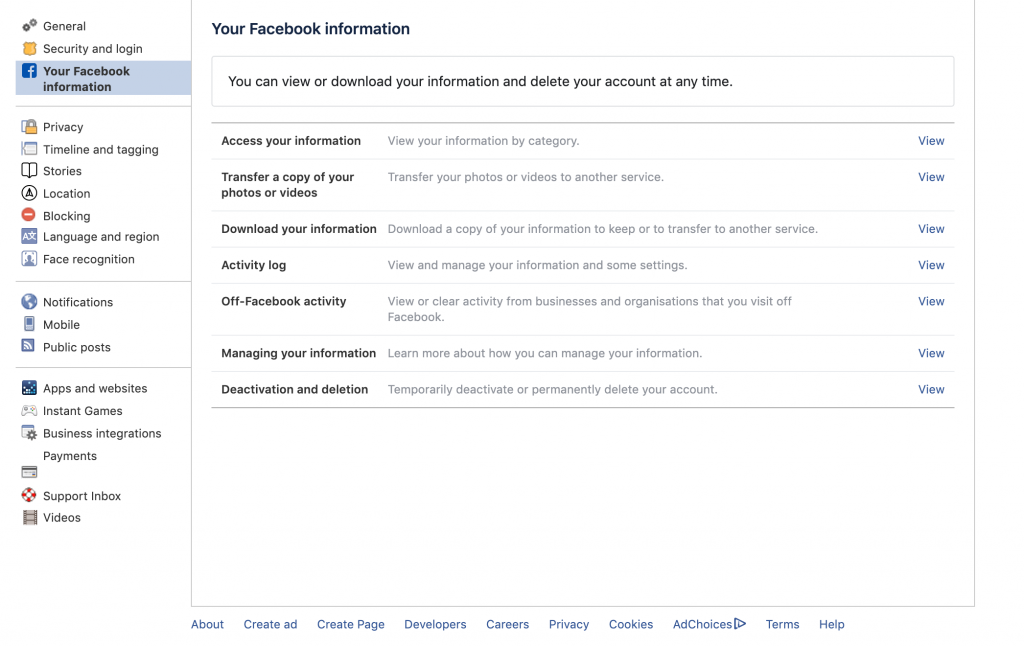

Facebook, not to be outdone, has enormous amounts of information on its users. Since the implementation of the GDPR (see ‘GDPR Quiz‘), online platforms are now obligated to offer users ‘data portability’. This means that users need to be able to download their data in an easily understandable format at any time. Google did this with Takeout. Facebook has the same kind of service. By going to Your Facebook information, you can download your entire history on the platform. You can also check this directly online, which is what we will do. Ask participants to go to their account settings on Facebook, select the third item on the upper left-hand menu, ‘Your Facebook information’.

Click on ‘Access your information’. Amongst these are:

Click on ‘Access your information’. Amongst these are:

- Posts

- Comments

- Photos and videos

- Likes and reactions

- Messages

There is one particularly interesting section: ‘Messages’, which contains every message you have sent and received on the Messenger app. On your phone, when you authorise the application Facebook Messenger to manage your messaging, these are saved on Facebook’s servers. Another interesting section is ‘Ads and businesses’ which you can find further down the list under ‘Information about you’. This shows all your ‘ad interests’ Facebook has on you through things you have liked or interacted with, as well as a list of advertisers and businesses who will target ads at you based on this information which they have in their databases. Ask the group to check their own information. Here again, you could help them to better protect their account and restrict their authorisations.

Walking debate

Now that participants have been able to see what data platforms like Facebook and Google have on them, it’s time to get them to react. Organise a moving debate. The objective of a walking debate is:

- Encourage participants to reflect and think critically

- Stimulate interest in the subject, questioning and debate amongst the group

- Unravel prejudices

- Motivate potential answers and thought processes

Present a series of statements. For each assertion, each participant will have to position themselves physically:

- To the right of the facilitator, if they agree

- To the left, if they disagree

- No one is allowed to stay in the middle (no opinion). The need to move pushes them to choose a side.

After each statement, once everyone has moved where they want to go, ask someone why they positioned themselves for or against. During the exchanges, there are three rules:

- A participant may only speak once per debate

- Arguments given should be based on the statement and not on the most recent assertion by another participants. Arguments should not be responded to.

- Participants are allowed to change side if they are convinced by an argument. Positions can be changed as many times as desired.

The debates

Once participants understand the idea of a walking debate (and they have clearly understood the fact that they can change sides during the debate, during an assertion, without waiting for the end of an argument), begin!

Facilitation tips: Don’t force participants to contribute. This could make some people uncomfortable, and so they may not dare to move. Instead, ask ‘who would like to go first?’ then leave the debate occur naturally.

Allow participants to say their piece, move on to the next speaker after a suitable amount of time has passed. and encourage the shyest to speak where appropriate. Elsewhere, it is possible that participants may feel ‘obliged’ to be against the data collection, against GAFAM, etc. Remind them that they are allowed to feel unconcerned — what matters is to make informed decisions. Use these statements, presenting them one by one.

1.Facebook or Google harvesting users’ personal data is a breach of privacy.

2.If Facebook or Google use and sell a user’s data, that user should get a portion of the revenue.

3.All personal data have value. They should not belong to Facebook, Google or any other company, but be put in public domain.

4.If a user doesn’t want Facebook or Google to know their secrets, the simplest thing to do would be to not use these services.

5. Personal data should not belong to companies. It should be put under the control of a third party, the state for example.

6.A user, continuing to use services like Google and Facebook, decides to enter false information so their real data will not be exploited.

7.I use these platforms. It doesn’t bother me one single iota that they have so much information on me. It’s the fair price I pay for using their free services.

The following three propositions correspond to the three general camps of personal data management:

1. Selling with consent/individual user data property rights, as argued by the report from the think tank Generation Libre. The likes of Google and Facebook pay users for their data. This approach comes up against ethical problems and is totally incompatible with the GDPR as it currently is. As stated by the European Data Protection Board: ‘Considering that data protection is a fundamental right guaranteed by Article 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, and taking into account that one of the main purposes of the GDPR is to provide data subjects with control over information relating to them, personal data cannot be considered as a tradable commodity. Data subjects can agree to processing of their personal data, but cannot trade away their fundamental rights’.

2. Online privacy militancy, often associated with organisations like Electronic Frontier Foundation. This approach would restrict the current behaviour of Facebook and Google as it is felt to be too intrusive or disrespectful of privacy.

3.The opinion shared by Belorussian researcher Evgeny Morozov, according to which ‘data is an essential, infrastructural good that should belong to all of us (…) Instead of us paying Amazon a fee to use its AI capabilities – built with our data – Amazon should be required to pay that fee to us.’ Morozov thinks that we cannot avoid having such masses of personal data being used by tech companies, but that data property rights need to be revised for the benefit of all.